September 2000: The following is the brochure that launched new strategies designed to catalyze the profound transformation in gender relations required to break the cycle of hunger in Bangladesh. The strategies have evolved and grown since then, but the following provides an excellent introduction.

Table of Contents

- Unlocking the full potential of Bangladesh. The greatest obstacle to progress in Bangladesh is the subjugation of women that is pervasive in the country. Grassroots women are on the frontlines of the action that must be taken for Bangladesh to achieve a new future.

- Lifetime of subjugation. Every phase of a woman’s life is shaped by malnutrition, the denial of selfhood and lack of voice in the decisions that affect her life.

- The cycle of malnutrition: determining factor in Bangladesh’s future. Bangladesh’s rates of malnutrition are the highest in the world because the subjugation of women in Bangladesh is among the most severe.

- Women – Bangladesh’s invisible producers: unrecognised, unvalued and unsupported. In addition to her many household responsibilities, the Bangladeshi woman is a key producer of food and contributor to family income.

- Violence and the threat of violence to women are endemic in Bangladesh, and hold the social and economic subjugation of women in place.

- Women: equal before God / equal before the law/unequal every day of their lives. Social customs that discriminate against women are often falsely justified as part of religious teaching.

- Awakening to a new possibility. Sparked by an historic process of global activism, humanity is now recognising that women’s full equality and participation are pre-conditions to human progress.

- Local democracy. Establishing effective local democracy, including full participation by women, is critical for Bangladesh’s future.

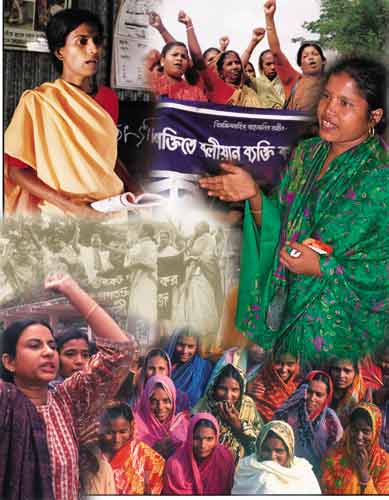

- Women as change agents. Despite enormous obstacles, grassroots women are addressing key issues of rural development and creating a society where hunger can truly end.

- Agenda for action. There are ten critical actions that must be taken in Bangladesh to ensure equity and opportunity for women.

- Women as Change Agents Campaign. The Hunger Project has launched a new strategy to empower grassroots women as change agents for a new future in Bangladesh.

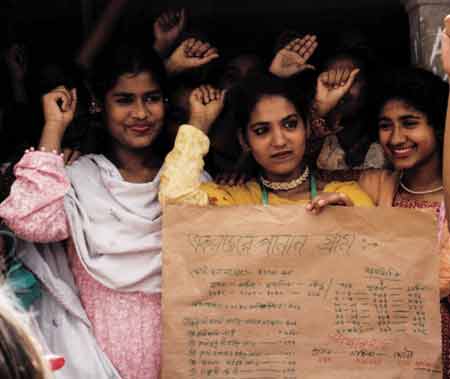

- National Girl Child Day. A key strategy to promote and defend the rights of girls.

Unlocking the Full Potential of Bangladesh

Bangladesh faces almost insurmountable challenges. Its large population – 128 million people – lives in an area the size of England and Wales, giving it one of the highest population densities in the world. Bangladesh’s geography makes it prone to natural disasters, such as flood and hurricanes. As very young country – winning independence only in 1971 – Bangladesh was immediately confronted with a severe food crisis. The nation lacks the well-developed industrial and institutional bases that many nations rely on for development. Educational levels are very low. At the birth of Bangladesh, some experts even questioned – can this nation survive?

Those who doubt Bangladesh’s future have never met the Bangladeshi people. The Bangladeshi people possess extraordinary resilience and creativity, and irrepressible spirit. Bangladesh’s proud and homogenous society has met challenge after challenge – strengthening people’s determination to build a better future. Bangladesh has established democracy, and achieved near food self-sufficiency and modest but steady economic growth. In addition, Bangladesh has built up a remarkable system of emergency preparedness and response. Despite cultural obstacles, it has made dramatic progress in family planning. Bangladesh has been the environment for globally-important breakthroughs in development, such as microcredit, oral-rehydration therapy, grassroots schooling and large-scale social mobilisation campaigns.

Bangladesh, however, has not made significant progress in overcoming the abject poverty and malnutrition of its people. Despite massive infusions of funding by international donors and the dedicated efforts of NGOs, the people of Bangladesh continue to suffer some of the highest child malnutrition rates in the world, almost twice as high as sub-Saharan Africa.

Bangladesh pays a terrible price for allowing malnutrition to persist. Malnourished children have lower IQs and suffer developmental and health problems that ultimately translate into less productivity – in a country that is already on the edge of survival.

The principle obstacle to ending malnutrition in Bangladesh – and thus unlocking the full potential of the Bangladeshi people – is the traditional subjugation, marginalisation and disempowerment of women that pervades Bangladeshi society.

For centuries, many women in Bangladesh have led lives of almost unimaginable isolation, malnutrition and powerlessness. Songs, proverbs and distortions of religious teachings have reinforced traditions that devalue and deny self-hood to one-half the population. These forces are further reinforced by the economic tyranny of dowry, and by physical violence. The presence of women heads of government in South Asia says more about the vestiges of feudalism that keeps power in the families of their husbands and fathers than it says about the status of women.

In these conditions, women are taught to “eat last and eat least” – giving the best food to boys and men, even when women are pregnant and nursing. Studies show that Bangladesh’s exceptionally high rate of malnutrition is a direct result of the severe subjugation of women.

Today, there is a new opportunity. In recent years, there has been a shift in consciousness of the women in Bangladesh. Through interacting with each other, with NGOs and with global communications media, the women of Bangladesh have been part of a worldwide awakening of awareness about women and their role in society. For the first time in thousands of years, women in Bangladesh are stepping out of their homes – earning income – and expressing their leadership. Grassroots women are banding together, forming self-help groups and associations, and running for seats in local government. Women today are challenging their traditional roles in ways unthinkable to their mothers.

Women as change agents. As Bangladeshi women gain this new awareness, they take action. When women gain voice, they decide to space their children, and have fewer children. As they gain information on nutrition, they improve the health of their families. As they earn income themselves, they see the value of education for their daughters, and use their income to keep their daughters in school. As they form self-help groups with other women, they are able to reach out to more and more women. Millions of these actions, taken every day, add up to a new future for Bangladesh.

The changes that need to be made for improving the health and nutrition of Bangladesh, must be made by these women. They are the ones on the front lines of what must be done to achieve a healthier and more prosperous life for their families, their villages and the nation.

Just as there were women on the frontlines of Bangladesh’s liberation struggle in 1971, today it is courageous women who are on the frontlines of Bangladesh’s second liberation – the liberation from hunger and abject poverty.

It is almost unimaginable – but true – that at the dawn of this new millennium, the deeply entrenched discrimination against women that has persisted for thousands of years is now beginning to change – and the change agents are the impoverished, illiterate, malnourished women themselves. All those who stand for a new future for Bangladesh must make the empowerment of these courageous women their highest priority.

A lifetime of subjugation

“Today women are still being discriminated against and

Sitara Begum, women freedom fighter in 1971 war for Independence

deprived…I can’t give any satisfactory answer when my daughter asks

me why things are not really different in an independent country

from the days of Pakistani subjugation.”

A female in rural Bangladesh faces some of the harshest discrimination in the world. Every phase of her life is shaped by malnutrition, the denial of selfhood and the lack of voice in the decisions that affect her life.

The pervasive social conditions that subjugate women are expressed and reinforced by the institution of dowry. Having a girl is a great burden, while having a boy is a great asset. Dowry has been illegal since 1980, yet its practice is steadily increasing.

Throughout her life, the nexus of social and economic forces that subjugates women is enforced by violence and the threat of violence (see page x).

- Unwanted before birth. A baby girl in Bangladesh is born into a family that had wished and prayed for a boy. Because of mistreatment of girls nearly from birth, Bangladesh’s population has dropped from a “natural” ratio of 1,003 females per 1,000 males to 947 women per 1000 men.

- Deprived as a baby girl. Girls are fed less food, and lower quality food. When girls become ill, they are much less likely to receive medical care than boys – resulting in under-five mortality rates 11 per cent higher for girls than boys.

- Childhood of drudgery. By age five, girls carry adult responsibilities both inside and outside the home. At home, she cares for her younger siblings, and for her sick or pregnant mother. Outside, she fetches water, firewood and fodder. Education and play are unthinkable.

- Adolescence: health crisis and sexual violation. Girls who reach puberty face a new set of harrowing and untreated problems of physical and mental health. At the very time her body need more nutrition, she receives less. Her physical and mental health deteriorate, and she may feel worthless and unwanted. Adolescent girls run high risks of sexual assault.

- Marriage: a new cycle of subjugation. She is married young, to a man who is an average of 8 years older than she. Early and frequent pregnancy – often with no medical care and over which she has little choice – puts her health at risk. She is isolated – frequently not permitted to leave the household, and thus unable to be assisted, supported or protected by other women.

- Adulthood: overworked and undernourished. A woman in Bangladesh works twice as many hours as her husband (see page 10). Her triple burden – child-rearing, work in the household and paid labor outside the home – goes unrecognised and unsupported. She is malnourished throughout her life (see page 8), even while pregnant and nursing.

- Mistreated in widowhood: The social status of a widow is the lowest of all women in Bangladesh. She may be mistreated or regarded as dishonourable if she tries to support herself by working outside the home. Although Muslim law dictates that she receive a share of her husband’s property, in reality only 32 per cent of widows receive their rightful inheritance.

The Cycle of Malnutrition: Determining Factor for Bangladesh’s Future

The exceptionally high rates of malnutrition in South Asia are rooted deep in the soil of inequality between men and women.

UNICEF, “The Asian Enigma,” The Progress of Nations 1996

Bangladesh has the highest rates of malnutrition in the world. The vicious cycle of malnutrition among the women of rural Bangladesh perpetuates the cycle of malnutrition and poverty for both men and women in all of Bangladesh.

When children are born malnourished and underweight, they are at severe risk in all areas of personal development, health and mental capacity. They are physically weak, and lack resistance to disease. They face a lifetime of disabilities, a lowered capacity for learning, and diminished productivity.

The cost of this deficiency to Bangladesh, solely in economic terms, has been estimated to be as much as US $22.9 billion in the next ten years’ time. This means an annual loss of Taka 13,000 crore every year, a figure equivalent to the draft annual development budget of Bangladesh 1998-99.

This reality is a clear and direct result of the subjugation, marginalisation, and disempowerment of women throughout their lives.

We should not need to focus exclusively on women as mothers in order to be committed to transforming their status. Yet, in their role as mothers, they do represent the most critical link in the chain of human well-being and development.

It is widely recognised that the health and nutritional status of a pregnant woman dramatically affects the health of her baby. A more accurate scientific understanding, however, indicates that this is only part of the story. The truth is that a woman’s health, from the time she is in her own mother’s womb, is the single most important factor in determining the health of her child.

With this knowledge, it is clear that traditional responses to child malnutrition, such as simply providing nutritional supplements to pregnant women, are both inadequate and ultimately futile. If Bangladesh is to interrupt the cycle of persistent hunger, the lifetime health and nutritional status of women must improve dramatically.

This, in turn, means transforming the way women are treated in the family and society as a whole:

- No longer can she eat last and least, taking whatever is left over after feeding the husband and sons.

- No longer can teen-age girls facing the stresses of puberty also expect to face deprivation, assault and pregnancy.

- No longer will a lifetime of malnutrition be the primary legacy that Bangladeshi women pass on to their children.

Underweight at birth

- 50 per cent of Bangladesh’s babies are underweight at birth due to the malnutrition and ill-health of their mothers.This compares to 33 per cent of those born in India, 15 per cent of those born in Africa and 7 per cent of those born in the United States.

- Babies born underweight face physical and mental health problems thoughout their lives.

Eats last and least as a girl

- She and her mother eat last and least in the family. The food they eat is less nutritious.

- 56 per cent of Bangladeshi children are malnourished and underweight under age 5, compared with 53 per cent in India, and 32 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa. Severe malnutrition is worse among girls than boys.

- Chronic malnutrition can result in stunted growth and incomplete physical and mental development.

Unsupported in Adolescence

- She receives no special food or care in adolescence – when her body requires it most for growth and attainment of sexual maturity.

- Married as a teen, she becomes pregnant before her body is ready.

- Lack of nutritional support for adolescent development results in reproductive health complications and increased mortality.

Malnourished in motherhood

- 70 per cent of Bangladeshi women are underweight and malnourished. By contrast, the proportion of underweight women in sub-Saharan Africa is only 20 per cent.

- She receives no extra food or special care in pregnancy, although her nutritional requirements increase dramatically. She gains only half of the weight necessary to have a healthy birth. 53 per cent of pregnant Bangladeshi women are anemic.

- She continues her backbreaking work throughout pregnancy, while seldom receiving any prenatal care.

- Her malnutrition will be passed down to the unborn child in her womb.

Women – Bangladesh’s invisible producers:

Unrecognised, Unvalued and Unsupported

Rural Bangladesh depends on its women for survival.

Its children and families are fed, clothed and sheltered by the labor of women. Its water and fuel are gathered by the hands of women. Its family farms and rural economy are productive because of women’s work.

Yet, when men are asked, they say women do nothing at all.

Because of women’s low social status, their work goes unacknowledged, unvalued and unsupported.

Women carry a triple burden. They make indispensable contributions in all areas of rural life and economic activity, particularly in agriculture, income-generating activities, and household maintenance.

Agriculture

- Women constitute 46 per cent of the farming population.

- In households with no or little land, 60-70 per cent of women work as agricultural wage laborers.

- Women in Bangladesh are instrumental in key areas of agriculture production. Bangladeshi women do:

- 73 per cent of the work of growing vegetables and spices

- 98 per cent of the poultry farming and 48 per cent of the cattle farming

- 89 per cent of the husking, drying and boiling

- 86 per cent of the processing and preservation.

Income-generating activities

- Women are critical income earners for the family. They engage in small business ventures including weaving, pottery, vegetable oil extraction, and fish farming.

- Women comprise between 80 -90 per cent of the workforce in garment manufacturing– Bangladesh’s largest export industry.

- Women contribute nearly half of the total work hours in sericulture – including silkworm and cocoon reeling

- Women comprise 53 per cent of the total employees in cottage industry, and 17 per cent in large scale industry.

Household maintenance

Women and girls have primary responsibility for all household work, and caring and providing for their families. They are traditionally responsible for water, fuel, and fodder (animal feed).

- Women hold full responsibility for cooking, cleaning, washing, and caring for children, the sick and the elderly.

- Cow dung is the largest source of tradition fuels in the unorganised sector. Women are responsible for all the work of dung collection.

- Women manufacture critical equipment within the home. They manufacture the clay stove they cook on, the bamboo tray they winnow with, and the mats they sit and sleep on.

- Women may cook for more than 3 hours per day, burning wood, dung and crop residues. The smoke they inhale is equivalent to smoking 20 packs of cigarettes per day. It causes eye and respiratory problems, bronchitis and lung cancer.

Unequal pay for Unequal Work

Despite their hard work, women are rarely compensated for their labors.

- In spite of their crucial contribution to family income generation, the average wage for women’s non-agricultural work stands at a mere 42 per cent of the average wage for men.

- Women share only 23.1 per cent of total earned income in the country.

- When women control their own income, they invest in the well-being of their children and families, while men often spend earnings on themselves.

Quote

Women’s work in the rural households is so essential that they are the first to rise early from bed to work and the last to go to sleep…Yet, the fact remains that women’s work is neither measured in economic terms nor given due social recognition. So women themselves do not consider the value and importance of who they are and what they do.

Thomas Costa, Caritas Bangladesh,1999

Although women have been subjugated…their labour is actually the foundation of a society’s wealth.

Kathita Rahman, Bangladesh Institute of Labor Studies

Women: equal before God, equal before the law, unequal every day of their lives

The Quran affirms the fundamental equality of men and women. So does the Constitution of Bangladesh. Neither religious teaching nor government laws consider men to be in any way superior to women. In spite of this deep-seated truth, women in Bangladesh suffer from severe subjugation, and unequal treatment every day of their lives.

Equal in religion

And [as for] the believers, both men and women—they are friends and protectors of one another: they [all] enjoin the doing of what is right and forbid the doing of what is wrong.

Quran 9:71

I shall not lose sight of the work of any of you…be it man or woman: You are members, one of another.

Quran, 3:195

Because of a belief in a liberated, equitable and dignified position of women outlined in the Quran, many Muslims, men and women alike, are calling for reevaluation of attitudes and practices that, although done in the name of Islam, are actually contrary to the basic messages found in the primary sources.

To question and possibly oppose entrenched positions that are based on archaic law… or cultural trends, requires courage and conviction on the part of religious leaders. But this is necessary and worth any risks in order to enable women to achieve liberation through Islam as originally intended.

Muslim Women’s League, United States

Customs which subjugate women are not supported by the Quran. The essential message of Islam is the equality of all people – women and men – before God. Many Muslims have pointed out the progressive aspects of Islam, which granted rights to women in the 7th century that were denied to English women through common law until the 18th. Islam sees a woman, whether single or married, as an individual in her own right, with the right to own and dispose of her property and earnings. Religious teaching encourages women to take an active role in politics and society.

Narrow interpretation has distorted Islam’s message of women’s equality, and has used religion to justify the number of offences promulgated against women. In the name of Islam, women are denied their rights to divorce, child custody, and community property. Women who have dared to challenge rigid social codes have both been victims of violence and moral censure.

Equal by law

Women shall have equal rights with men in all spheres of the State and of public life.

Bangladeshi constitution, Article 28(2)

The Constitution and laws of Bangladesh, and the international declarations that it has ratified, guarantee women’s fundamental human rights. Bangladesh’s Constitution proclaims women’s right to life and the security of the person; equality before the law; protection by the law; and freedom of expression, association and religion. Bangladeshi law declares that violence against women, trafficking of women and girls, and traditional practices such as early marriage and dowry are illegal. International conventions which Bangladesh has ratified testify to the fundamental equality of women and men, and declare that nations must take action to eliminate traditional practices based in the inferiority or superiority of either men or women.

In practice, conservative traditions and misinterpretation of religion mean that women’s rights are violated in the “private sphere” of the home. Traditional courts have tried, convicted and sentenced women to death without legal authority. Yet, government has not strongly condemned, investigated, or prosecuted the perpetrators of these offences. With little knowledge about their legal rights, women are powerless to confront fundamental violations of their human rights.

Violence

“…Violence against women and girls, many of whom are brutalised from cradle to grave simply because of their gender, is the most pervasive human rights violation in the world today.

“Long after slavery was abolished in most of the world, many societies still treat women like chattel: Their shackles are poor education, economic dependence, limited political power, limited access to fertility control, harsh social conventions and inequality in the eyes of law. Violence is a key instrument used to keep these shackles on.

“Stopping violence against women and girls is not just a matter of punishing individual acts. The issue is changing the perception – so deep-seated it is often unconscious – that women are fundamentally of less value than men. It is only when women and girls gain their place as strong and equal members of society that violence against them will be viewed as a shocking aberration rather than an invisible norm.”

Charlotte Bunch, Executive Director of the Center for Women’s Global Leadership, in UNICEF 1997 Progress of Nations

–

Violence against Girls and Adolescents

Trafficking and Sexual Abuse

- Over the past decade, more than 500,000 Bangladeshi women and children have been trafficked – smuggled into prostitution or forced labour across country borders. Women are abducted and lured by traffickers through threats, physical force, illegal confinement and debt bondage.

- Half of 150 people interviewed in Bangladesh admit experiencing some form of child sexual abuse.

- 16.26 per cent of rape victims are minors

Child marriage

- 50 per cent of girls aged 15-19 in Bangladesh are currently or have been married.

- Many girls have their first child while they are still teenagers. Over 10 per cent of girls currently 15 have begun childbearing in Bangladesh, the highest known percentage in South Asia. These young mothers face the stresses and risks of childbirth before their bodies have matured, and have a high incidence of maternal mortality.

- The risk of maternal mortality is three times as high for 15-19 year olds in Bangladesh as compared to even slightly older married women, ages 20-14.

Acid Attacks

- Women are disfigured and sometimes killed by male attacks using sulfuric acid, a cheap and accessible weapon. Reasons are as varied as family feuds, inability to meet dowry demands, and rejection of marriage proposals.

- There were over 200 reports of acid mutilations in Bangladesh in 1998 alone. UNICEF believes the actual number of cases is much higher.

Violence against women

Physical abuse and domestic violence

- Bangladesh’s maternal mortality rate – at 440 deaths per 100,000 live births – is a leading cause of death. Yet, more women die from burns, suicide and injury than from pregnancy and childbirth.

- More than 70 per cent of women in some regions of Bangladesh suffer from domestic abuse.

- In 750 cases of family violence in Bangladesh, male relatives account for all but 29 cases of violence.

- Nearly 50 per cent of all murders of females in Bangladesh can be attributed to domestic violence.

Dowry violence and deaths

- There were 239 reports of dowry-related violence in 1998, an increase of 25 per cent from the year before. Because of the vast number of unreported incidents, this number is significantly higher.

- Physical and verbal abuse of wives due to non-fulfillment of dowry occurs in at least 50 per cent of recent marriages.”

Psychological abuse

- The United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women cites psychological harm as a major form of violence against women.

- Women suffer from belittlement, threats, taunting and confinement. This can lead to depression and even suicide.

Violence in motherhood

- Bangladeshi women 15-19 who are pregnant or have recently given birth are nearly three times more likely to die from violence than women of the same age who are not pregnant.

- Battered pregnant women are twice as likely to miscarry and four times as likely to have a low-birthweight baby.

- Children born to battered women are 40 times more likely to die in the first five years of life than children whose mothers are not battered.

Mistreatment in widowhood

- Widows in Bangladesh may be mistreated and secluded.

- A 1992 study of widows from four squatter sites in Dhaka found that 70 per cent of younger widows are victims of sexual attacks.

Awakening to a new possibility

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women…

Universal declaration of human rights, 1948

The subjugation of women is deeply ingrained in Bangladeshi society. It is so much a part of ordinary reality that it is largely unseen, un-examined, and unquestioned. Yet today, after thousands of years of suppression, the women of Bangladesh are awakening to a new possibility – a future based on self-hood, equality, and full participation. This awakening is part of a dramatic worldwide shift in consciousness about women and their role in society.

A global struggle and a global stand. The 20th Century saw the roots of women’s emancipation take hold in many parts of the world. One hundred years ago, in 1900, women had the right to vote in only one country – New Zealand. By the 1920s women had won the vote in Great Britain, most of Europe, and the United States. In 1948, the United Nations adopted The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, proclaiming for the first time in history the “equal rights of men and women.”

In the years that followed, the struggle continued and took on momentum. In 1972, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed that 1975 would be International Women’s Year, launching a historic series of international conferences dedicated to the proposition that the world community will no longer tolerate the subjugation, marginalisation, and disempowerment of one-half of humanity. Global women’s conferences were held in Copenhagen in 1980, in Nairobi in 1985, in Beijing in 1995, and in New York in 2000. Women’s issues moved to the forefront of the international agenda in global conferences on food, environment, population and human rights.

The shift in Bangladesh. Bangladesh has a history of women’s activism. It has only been in the last ten years, however, that this shift in thinking has begun to be felt throughout Bangladeshi society. There were some important precursors. Thanks to years of activism, Bangladesh made dowry illegal in 1980. In a 1978-80 two-year plan – women for the first time were referred to not as objects of welfare, but as actors in their own development. In the coming years, government plans called for women’s full integration in economic development, and as change agents in the development process.

In March 1997, the Prime Minister declared a Policy on Women’s Advancement that provides a comprehensive framework for women’s development in Bangladesh. With the reservation of 30 per cent of seats for women in local government councils, Bangladesh’s women – for the first time – have an opportunity to have a voice in local decision making.

Discrimination against women violates the principles of equality of rights and respect for human dignity, is an obstacle to the participation of women, on equal terms with men, in the political, social, economic and cultural life of their countries, hampers the growth of the prosperity of society and the family and makes more difficult the full development of the potentialities of women in the service of their countries and of humanity.

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 1979

Women’s rights are human rights and human rights are women’s rights

-Rallying call for women’s groups at 1993 World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna

The Shift in World Consciousness

1948: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaims “the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family.”

1975: The First United Nations Women’s Conference in Mexico City establishes the women’s movement as a global phenomenon, and launches the UN Decade for Women.

1979: The Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) calls on nations “to modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women…which are based on the idea of inferiority or superiority of the sexes.”

1980: The Second United Nations Women’s Conference in Copenhagen first addresses the issue of women and development.

1985: The Third United Nations Women’s Conference in Nairobi helps to catalyse the emergence of women’s NGOs worldwide.

1993: Women’s groups at the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna declare that women’s rights are human rights, and human rights are women’s rights.

1993: The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women proclaims that “violence against women constitutes a violation of the rights and fundamental freedoms of women.”

1995: The Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, calls for gender issues to be fully mainstreamed into government policies and actions – making women full and equal partners in society – and creating a strong platform for action and advocacy for women.

2000: Women mobilise in New York for Women 2000: Beijing +5, to hold governments accountable for the commitments they made at Beijing, and to address new issues of domestic violence, trafficking, HIV/AIDS and globalisation.

Local democracy in Bangladesh

Democracy at the village level is vital for ending hunger. As Nobel Prise winning economist Amartya Sen has written, “democracy is not only the goal of development, it is the primary means of development.” The complex and diverse challenges facing the rural people of Bangladesh can only be solved locally – by the people themselves. Only when there is effective local democracy – when people have real voice in the decisions that affect their lives, when they can mobilise and control their own resources and manage the programmes to meet the basic needs of the community – will they bring their full responsibility and creativity these efforts.

Democracy is new in Bangladesh. The current democratic structure was established in 1991, after years of dictatorship. Although elections are being held, democratic practices have not yet taken hold in Bangladesh. General strikes and violence take the place of debate. Habits of domination, patriarchy, feudalism, exploitation and corruption are endemic at both local and national levels.

Local democracy is even newer. In 1997, democratic decision making was extended to local levels, through legislation establishing elected local councils – Union Parishads. These democratic institutions are assigned responsibilities for promoting participatory action for economic development, health, education and other issues of immediate importance in the day-to-day life of rural people.

Women’s leadership. One of the most visionary provisions of the legislation is that 30 per cent of the seats in Union Parishads are reserved for women – providing grassroots women an unprecedented opportunity to participate in local decision making in Bangladesh. When women become elected representatives, it enables them to become change agents for development issues, as well as role models – pointing the way to what is possible in a future of women’s equality and full participation.

Limitations. These local democratic institutions are fragile. They exist only through legislation – which can change – rather than being enshrined in the constitution. Local democratic institutions have no guaranteed access to financial resources. Very little power has been transferred to local bodies from the existing administrative services to enable them to operate locally accountable programmes for health, education and development.

An important step. Despite their current limitations, these democratic local institutions are vitally important for four distinct reasons. (1) They provide a laboratory for the development of grassroots democratic values and processes. (2) They provide an opportunity for grassroots people to demand accountability from government. (3) They provide a forum for grassroots women to exercise and develop their leadership and (4) they provide leadership with the authority and influence for effective social mobilisation – that is, for mobilising the population for self-reliant action to meet local needs.

Support. Government, donor agencies, NGOs and all organisations committed to the well-being of grassroots people, must commit themselves to the success of grassroots democracy. NGOs – which often develop their own local structures – must commit themselves to work with and strengthen local democratic institutions. Government and NGOs must work together to provide every form of empowerment available – information, training and responsibility for local project management – in ways that maximise the chances for local democracy to succeed.

Women as change agents

Women as Freedom Fighters: During Bangladesh’s struggle for independence, women stood shoulder to shoulder with men. While the women of Bangladesh fought and died for freedom, few have been able to share the full fruits of that freedom. They remain marginalised and disenfranchised, as they had been throughout history.

Today, grassroots women are becoming a new generation of freedom fighter. Through participation with women’s groups, self-help groups, local democratic bodies and the growing emphasis on education for girls, women are stepping outside their homes and becoming agents of change for a new future.

History books may not record their names, yet when historians look back on the 21st century, they will likely record that the health and prosperity of Bangladesh were transformed by the committed action of tens of thousands of individual women – who reached out to other women – to create a new future.

Grassroots women form women’s self-help groups, create their own enterprises and increase their incomes. They facilitate other women to step out of their household, become literate and learn their legal rights – in the home and in society.

Women face harsh opposition: The forces of patriarchy and fundamentalism continue to resist women’s participation in their communities and strongly oppose women taking leadership roles. Women who take action as change agents are often victims of physical attack, violence and humiliation.

Women are making a difference. Against all odds, women are making headway in areas of immediate concern to their families and their villages. These issues, often ignored by men, range from health and sanitation to campaigns against dowry and domestic violence. At the dawn of this new millennium, many of the entrenched social evils that have persisted for thousands of years are beginning to change.

Women are transforming the development agenda to address issues critical to village life:

- Health: Women – who are most often affected by poor health throughout their lives – take a stand for better nutrition, sanitation facilities, safe drinking water, and access to reproductive health care essential for healthy families and communities.

- Education: Women organise literacy courses for other women in the community. They ensure that schools are built for children, that teachers are held accountable, and that both girls and boys attend.

- Income generation: Women form self-help groups and credit organisations among themselves to increase family income. Women leaders organise skills training for the women of the community.

- Addressing social evils: Women take action to address crucial social issues such as dowry, domestic violence, child marriage, and child labor. They ensure that women know their rights, and have access to information. They commit themselves to include traditionally excluded minorities.

- Redefining leadership: Women are changing the nature of leadership, incorporating values such as honesty, openness, patience, collective support, inclusion, and accountability.

- Changing village dynamics: In even the most conservative villages, women’s leadership unleashes a process of change for the whole community. Women leaders facilitate other women to step out of the home, become literate, and contribute to the community. They create new partnerships with men in their families, helping to dissolve old patterns of discrimination and abuse.

Quote:

Women have plans for themselves, for their children, about their home…They have a vision.”

-Grameen Bank’s Prof. Mohammed Yunus

Agenda for Action

Ten critical actions that must be taken for Bangladesh to have a new future

The future of Bangladesh depends on the future of its women. Without a drastic change and intervention in the lives of women, Bangladesh will continue to fall drastically short of its true potential.

This transformation will require support at all levels of society – from government leaders to village people. It will require an intense personal commitment – by women and men – to call into question the roles that society has delineated for them.

Women in Bangladesh will need to find the courage to rise above the subservient, subordinated roles that are dictated to them by society. Men will need to become sensitive to the ways in which they and their society discriminate against and disable women, and to have the courage to change these ways. Together, they must forge a new partnership based on equality, for the future of their families, their communities and the nation.

- Women’s Organisations: Women must be organised into self-help groups and community organisations. Women’s organisations are key to enabling women to come out of their homes, identify their common problems, and take joint action for solutions.

- Income Generation: Women must be provided with resources and skills training which enable them to participate in small enterprise. When women increase their own income, they invest in the well-being of their families.

- Better Nutrition: Families and communities must ensure women’s equal access to food throughout their lives. Women must have the information they need to make appropriate decisions about nutrition.

- Basic and Reproductive Health: Women must have access to basic health care at all stages of life—from infancy, to adolescence, to adulthood. In addition, they must have access to reproductive health—including contraception, pre-natal care, and information on child spacing and the harms of early marriage.

- Violence and Trafficking: Bangladesh must adopt “zero tolerance” of trafficking and violence against women. Men must change their behaviours. Families must treat violence in the household as a criminal act. Police must ensure that women’s complaints are heard, respected and acted upon promptly. Government must prosecute each and every case of violence against women to the full extent of the law.

- Education: Local communities must have the resources and accountability to ensure basic literacy and numeracy for girls and women. When women and girls are educated, this translates into lower population growth, reduced child mortality, lower school dropout rates, and improved family nutrition.

- Information: Women must have access to clear and accurate information on education, health, sanitation, nutrition, legal rights, and religion versus custom. Women leaders must ensure that this information is communicated orally to women who are illiterate.

- Freedom of movement: Women do not violate religious teaching by participating outside the home in economic and social activities. Women must have the opportunity to organise together and to participate in educational, health, religious, social and income-generating activities.

- Shared responsibility for household work: Men and women have equal rights and responsibilities to participate in the community. Therefore, men must share in household and family responsibilities so that women have the opportunity to exercise that right.

- Participation in local government: Without women’s participation in local government, basic issues for a healthy community are not addressed. Communities must commit themselves to overcoming the obstacles to women’s full participation in local government.

The Women as Change Agents Campaign

The major obstacle to a hunger-free society in Bangladesh is the subjugation of its women. Therefore, The Hunger Project is launching a co-ordinated, strategic campaign of action to empower women as key change agents for a hunger-free Bangladesh.

Animator trainings: The centerpiece of our new strategy is to have as many women as possible trained and empowered as agents of change in their villages – individuals that we call “animators.” The Hunger Project provides an intensive 4-day animator training and an ongoing support system of empowerment. In order to expand our ability to train more women animators, The Hunger Project is training a growing team of women to lead the animator training.

Animator empowerment: To strengthen and support women animators month after month, The Hunger Project has launched an Animator Empowerment programme – regular forums for women animators to come together, learn more, organise group action and support each other as leaders.

Information empowerment: The Hunger Project is creating handbooks of basic information of importance to women. These handbooks, in simple Bangla, empower animators from The Hunger Project and other organisations to educate women – door to door – about their most basic rights starting with the fact that, under the law, women are full and equal citizens. The handbook also tells them how they can access critical resources for health, education and nutrition.

Partnership with government: The Hunger Project will work in partnership with government to utilise government personnel and facilities for the empowerment of women as change agents in their villages. In particular, we will work with government to provide effective training to women who are elected to serve in local democratic bodies.

Transforming mindsets: The Hunger Project will work with government, media, other NGOs and its vast movement of volunteers to alter the prevailing mindset that holds women as less valuable than men. One key element of this campaign is National Girl Child Day.

“Investment in the education of girls may well be the highest-return investment available in the developing world.”

Lawrence Summers, then Vice-President of the World Bank, 1992

The future of Bangladesh resides in the future of its girls. As long as girls are treated as inferior and less valuable than boys, malnutrition will remain high and Bangladesh will suffer impaired economic growth. “National Girl Child Day” is a national strategy to cause a breakthrough in the status of girls in Bangladeshi society.

September 30 each year will be National Girl Child Day. National Girl Child Day has been chosen as one day of the annual Children’s Rights Week.

Actions are being organised at both the national and local levels.

National level

- A unified campaign. The Hunger Project is working with a broad network of government ministries, NGOs, women’s organisations, schools, colleges and the media to awaken people across the nation to the critical importance of providing better health, education and nutrition to girls as the highest leverage investment for the future of the country.

- Rallies and marches. In Dhaka, as well as in remote rural areas, organisations will rally their constituency to hold teach-ins and marches in support of National Girl Child Day.

- Media coverage. National Girl Child day will generate powerful media coverage in newspaper, television and radio – educating the public on the critical importance of this issue.

Local level

A crucial element of the National Girl Day Strategy is to fully involve Bangladesh’s rural population—the vast majority of the country’s people.

- Thana-level celebrations of National Girl Child Day are being organised with people’s associations, NGOs, and local government so that all people in the nation have the opportunity to participate.

- National Girl Child Day essay contests will be held in schools across the country. Both boys and girls will win prize for writing about the importance of better health and education for girls in Bangladeshi society.

- Hunger Project volunteers will take a leadership role to ensure that the National Girl Child Day celebrations reach out to villagers in every district of the country.